The Evolution of Visual Information Encoding (EVINE)

Language leaves no trace in the fossil record. However, an important component of the human language capacity, symbolic combinatoriality, might have “fossilized” after all.

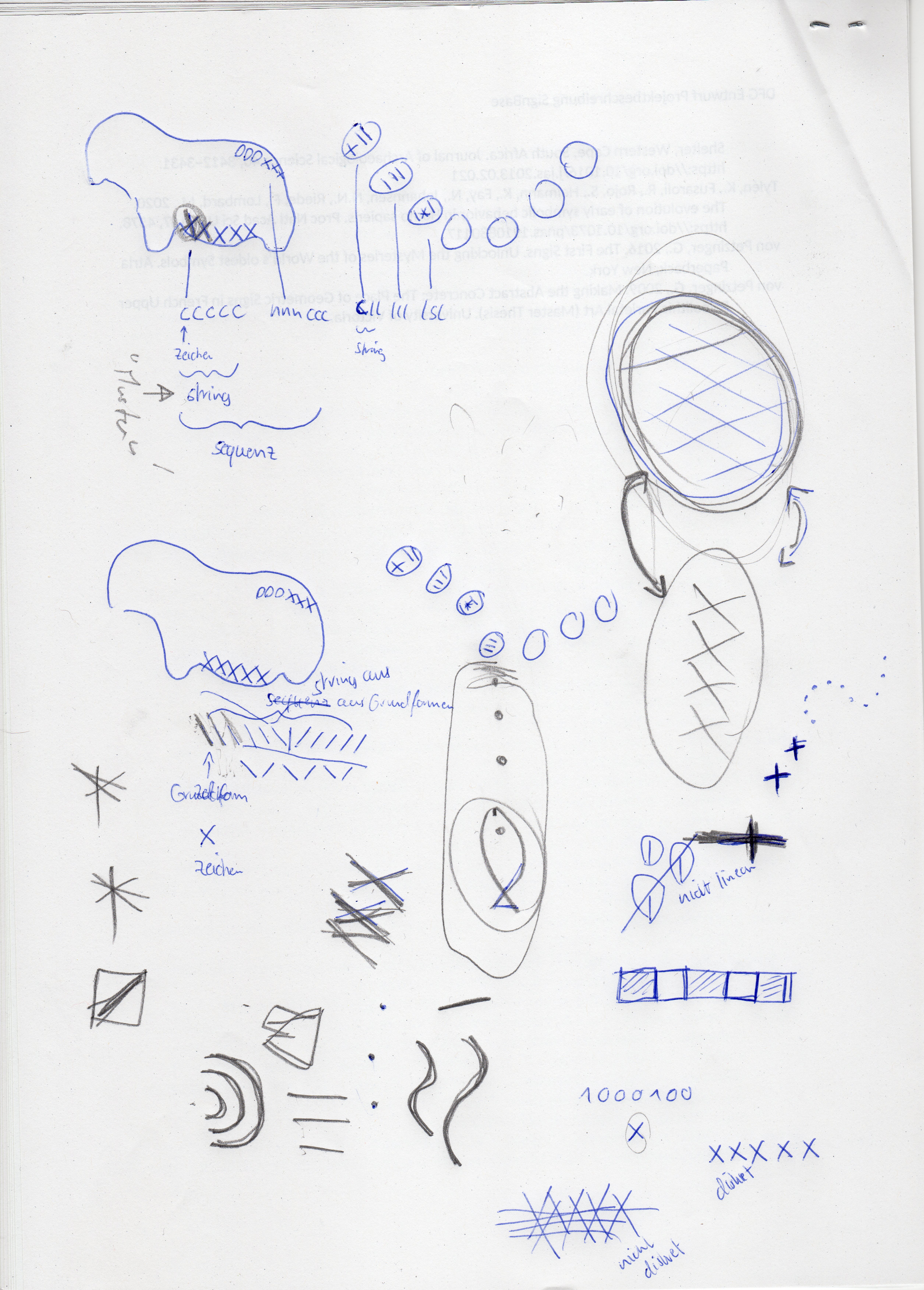

In the Paleolithic, hominins have embarked on their journey from Africa into the rest of the world. On their way, they have left artefacts which provide a window into their mind. Some of these bear early examples of visual information encoding: geometric signs. Analyses of isolated archaeological finds currently suggest that these signs were used as artificial memory systems in the Upper Paleolithic of Europe around c. 45 000 to 11 000 years ago. The respective codes seem to have become more complex towards the end of this period. However, how to exactly quantify and model this complexification is an open research question.

The EVINE project proposes to marry the growing body of archaeological data with state-of-the-art tools from empirical linguistics to assess the Evolution of Visual Information Encoding (EVINE) in the human lineage. To this end, statistical measures based on information theory, quantitative linguistic laws, as well as classification algorithms need to be developed, and applied to sequences of paleolithic signs, ancient writing, and modern writing.

This can transform our understanding of how information encoding evolved from the first signs to the information age.